Suicidality and Behavioral Emergencies

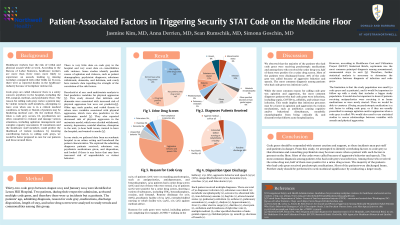

(186) Patient-Associated Factors in Triggering Security Stat Code on Medicine Floor

.jpg)

Jasmine Kim, MD (she/her/hers)

Resident

Staten Island University hospital

Staten Island, New York- SG

Simona Goschin, MD

Director Consultation Liaison

Lenox Hill Hospital

New york, New York - AD

Anna Lisa Derrien, MD

Associate Director of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry

Lenox Hill Hospital

New York, New York - SR

Sean Rumschik, MD

Psychiatrist

Lenox Hill Hospital

New York, New York

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

Background/significance: Healthcare workers face a disproportionately higher risk of violence in the workplace, compared to other professionals1. General medical hospitals use emergency code systems to call behavioral codes (or "security stat" code), which alert security and other medical staff, of patients with potential aggressive behavior. There is limited research published on these behavioral codes and the characteristics of patients that trigger them. In this study, we review the p</span>otential risk factors for behavioral codes by examining the patient data collected at a large urban hospital. Result: 76% of patients were on standing psychotropics. 56% of patients had a urine drug screen and out of those who were tested, 50% were positive for a tested substance. 78% of code grays were called due to verbal and physical aggression. The most common diagnosis patients received was infection (24%). Bibliography 1. Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers.

Method: A retrospective analysis of thirty-two behavioral codes (“code gray”) was conducted between August 2023 and January 2024. Data for twenty-five unique patients (excluding the repeat code activation) was reviewed. We analyzed patients' demographics, the reason for calling the code, length of stay, admitting diagnoses, medications, discharge disposition, history of psychiatric disorders and substance use, laboratory results etc., and compared it to the literature.

Discussion: While the most common reason for activating a code gray was agitation and aggression, the most common admitting diagnoses for patients who had code grays were infections, including sepsis, COVID-19, cellulitis, and urinary tract infection. All patients had a prior history of psychiatric diagnoses. Approximately 17% of patients received admitting diagnoses of substance use, but no patient had admitting diagnoses of primary psychotic illness. This result newly places infectious processes as a strong contributory factor in agitation and aggression, and clinicians and CL psychiatrists should be aware that infection may correlate with agitation and aggression in acute hospital settings via various mechanisms, such as metabolic encephalopathy from being critically ill, antibiotics causing cognitive and/or behavioral disturbances, and discomfort that follows acute hospitalization.

Conclusion: Code grays should be responded to with utmost caution and support, as these incidents may put staff and patients in danger. From this study, we attempted to identify factors that correlate with code gray so that clinicians and consulting psychiatrists may be more aware when a patient with such factors is present on the floor. Interestingly, infection was the most common diagnosis patients for whom code grays were activated, instead of substance use disorders. Further study is warranted to determine if infection is a significant predictor of behavioral codes in other settings. Also, studies on how infectious processes may induce aggression and agitation in patients should also be conducted to better understand and prevent code grays in patients with infection.

Presentation Eligibility: N/A

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: This study included patients from all backgrounds and may shed light on associated factors in violence on the medical floor. From the data we present, we found that patients who triggered the safety code were not those who were transferred from other areas of NY, but primarily those who came directly to the hospital, which is in an affluent neighborhood. This result may be able to destigmatize patients who are in low socioeconomic status.