Collaborative and Integrated Care

(049) Antidepressants in a Sickle Cell Center for Adults

Elizabeth Prince, DO

Assistant Professor

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland- PC

Pat Carroll, MD

Associate Professor

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

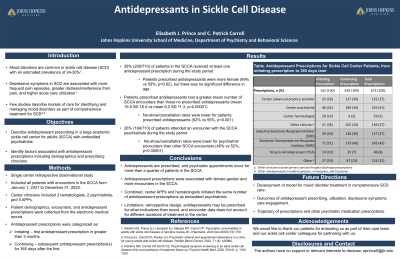

Background: Mood disorders are common in sickle cell disease (SCD), with an estimated prevalence of 24-30% (Mishkin et al, 2023). Few studies describe models of care for identifying and managing mood disorders as part of comprehensive treatment for SCD (Prince et al 2024, Robbins et al 2020). To our knowledge, there are no studies of medication treatment of mood disorders in patients with SCD. This study was undertaken to evaluate prescribing of antidepressants in patients at a large academic Sickle Cell Center for Adults (SCCA).

Methods: This IRB-approved retrospective observational study included all patients with encounters in the SCCA from January 1, 2021 to December 31st 2023. Psychiatrists are a component of the XXXX Sickle Cell Center for Adults (SCCA), providing direct clinical care, as well as mutual education and mentorship of other clinicians. Patient characteristics including age, SCD genotypes, and diagnoses, as well as outpatient encounters, prescriptions for antidepressants, and PHQ-9 screening results were extracted from the electronic medical record. Statistical tests will examine the association of antidepressant prescriptions with patient and encounter characteristics.

Results: Preliminary results indicate 137/741 (23%) patients seen in the SCCA during the study period received at least one antidepressant prescription. Most (72%) patients prescribed antidepressants had more than one prescription during the study period. Psychiatrists ordered about 60% of initial and 80% of subsequent prescriptions, with other clinicians ordering the remainder.

Discussion: Nearly a quarter of patients in the SCCA were prescribed medications for mood disorder during the study period. Psychiatrists ordered the majority of prescriptions, but were more likely to continue than initiate prescriptions. This suggests that mood disorder treatment begins before the initial psychiatric encounter in this clinic model. Future goals include determining which patient descriptive variables, if any, are associated with prescriptions, as well as examining timelines of prescriptions to further evaluate prescribing patterns and assess treatment continuity.

Conclusions: Understanding how antidepressants are prescribed in a SCCA can inform development of a model for mood disorder treatment in comprehensive SCD care.

References:

Mishkin AD, Prince EJ, Leimbach EJ, Mapara MY, Carroll CP, Psychiatric comorbidities in adults with sickle cell disease: A narrative review. Br J Haematol, 2023 Dec;203(5):747-759.

Robbins MA, Carroll CP, North CS, Psychological symptom screening in an adult sickle cell disease clinic and predictors of treatment follow up. Psychol Health Med, 2020. 25(10): p. 1192-1200.

Prince EJ, Carroll CP, Pecker LH, Psychiatric referral and appointment attendance in a clinic for young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2024. 71 (4): e30860.

Presentation Eligibility: Not previously published or presented

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: The topic of this submission, providing high quality depression care to people with sickle cell disease, advances diversity, equity, and inclusion. Deficiencies in sickle cell disease care, treatment, and research are recognized health disparities. In the United States, structural racism has created substantial barriers to access and delivery of care to people with sickle cell disease. This talk describes work to improve access to treatment of depression in this under-served population.